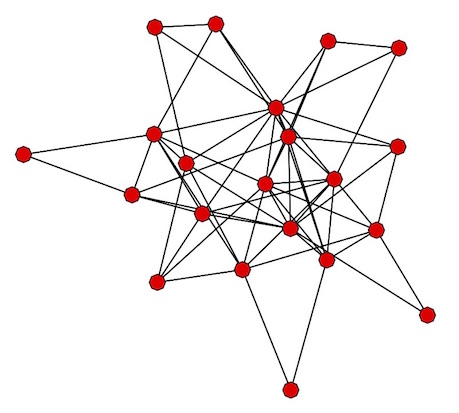

Networks, Grouping, and Disease Spread

I'm currently working with an international group of researchers to determine the effects of grouping and social network size on transmission dynamics of diseases. Although much of this work is currently comparative or simulation-based, I'm always looking for opportunities to "ground-truth" the models in the field (if you have a current project with social network data, but you're not quite sure what to do with it, I'd love to collaborate!).

Relevant Publications and Presentations:

1. More than just a numbers game: Populations, networks, and disease dynamics in primates 2015 Am Soc Primatol Annual Meetings

2. Infectious disease and group size: More than just a numbers game 2014 Phil Trans R Soc B

3. Do parasites constrain group size? A phylogenetic comparative study and meta-analysis 2012 Am Assoc Phys Anthropol Annual Meetings

Project Collaborators:

- Jennifer Fewell

- Lazslo Garamszegi

- Ferenc Jordan

- Charles Nunn

- Joanna Rifkin

- Jennifer Verdolin

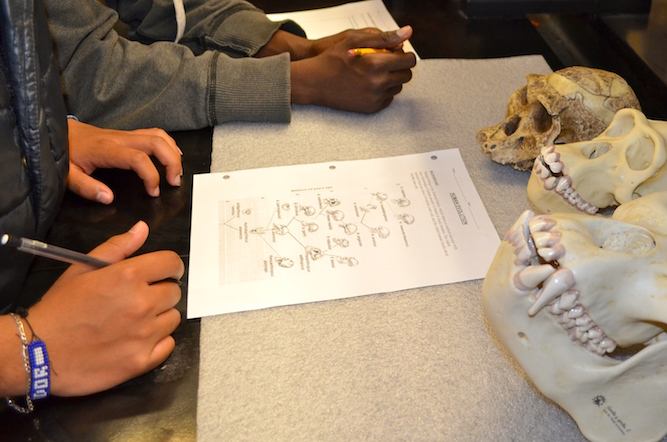

Skulls in Schools: K-12 Outreach

An integral part of my graduate education has come from middle-school and high-school students. For the past 3 years, I've coordinate visits with local teachers in Boston area schools to give interactive guest lectures to students. Through meeting with teachers to develop curriculum, I'm able to cooperatively identify "gaps" in state Biology standands, as Human Evolution is considered, and to fill in these gaps with my lectures. I also conduct before-and-after surveys with the students in each of these lectures to discover what worked and what didn't, and I'm able to adapt my teaching to the audience based on information that I receive from teachers.

Relevant Publications and Presentations:

Project Collaborators:

- Eric Castillo

- Erik Otarola-Castillo

The Evolution of Cooperation

![By Anna Bauer (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](img/coop_res.gif)

Large-scale cooperation, or the willingness of individuals to incur costs in order to help others, is a defining trait of the human species. However, cooperation poses a theoretical puzzle: since it is individually costly to cooperate, it seems that natural selection should favor non-cooperation (defection). Recently, it has been proposed that coordinated, collective punishment by cooperators of defectors can allow cooperation to invade a population of defectors. Along with David Rand, I examined the effect of allowing coordinated antisocial punishment on the emergence of cooperation. Our results suggest that punishment confers no competitive advantage when it is a strategy available to both cooperators and defectors. While coordinated prosocial punishers can invade a population of non-punishing defectors, they cannot invade a population of coordinated antisocial punishers. These results question the conclusion that coordinated punishment played a central role in the evolution of human cooperation, and highlight the importance of not arbitrarily excluding antisocial punishment strategies from evolutionary models.

Relevant Publications and Presentations:

Project Collaborators:

- David Rand